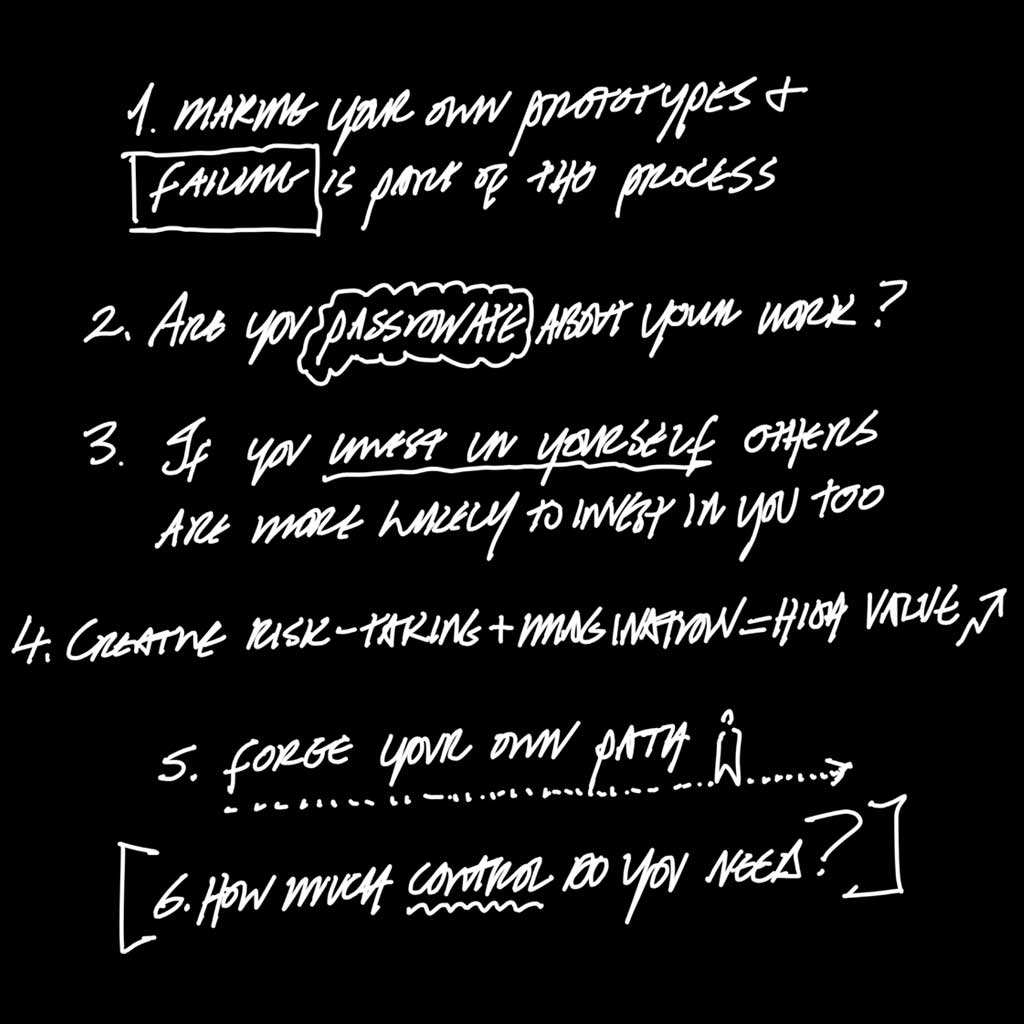

On the importance of making your own prototypes and failing as part of the process:

“Of the 5,127 prototypes I made in the coach house of the cyclone technology for my first vacuum cleaner, all but the very last one were failures. And yet, as well as painstakingly solving a problem, I was also going through a process of self-education and learning. Each failure taught me something and was a step towards a working model. I have been questioning things and learning every day ever since. This, of course, is what engineers do, beginning as often as not as those children whose curiosity leads them to take toys and clocks and radios and, indeed, the very latest technology, apart while not necessarily being able to put them back together again. Having studied and practised engineering, there is nothing quite as instructive as seeing a test fail before your eyes. This is why at Dyson we don’t have technicians. Our engineers build their own prototypes and then test them rigorously so we properly understand how and why they might fail. The action of making the parts to do a test is also really important. It allows you to spot opportunities to do things in different ways, hopefully for the better. Learning by doing. Learning by failing. These are all effective forms of education.”

This is important for all would-be creators, inventors, designers and entrepreneurs to understand. Making your own physical prototypes is one of the most instructive things you can do. Making is where theory and reality intersect. Make your own things, as much as you can, and learn directly from them. More is learned at this intersection than almost anywhere else.

Are you truly passionate about what you do?

“In its early years I chaired the Innovation RCA Board, which ran this area of the college. It has been hugely successful. Silicon Valley investors are lucky if 10 per cent of the start-ups they back succeed, whereas the RCA incubator unit has a 90 per cent success rate. In fact, the college as a whole has twenty times more start-ups emanating from their courses than the second highest university in the field, Cambridge. I believe this is because the product ideas come from imaginative engineers and designers with a burning passion for their products, rather than from people just trying their luck at being entrepreneurs.”

Passion for what you do increases your chances for success. When you are passionate you commit fully to your ideas, and full commitment is needed because making things is difficult work. When the inevitable obstacles appear, passion will help you overcome them.

If you invest in yourself others are more likely to invest in you too:

“Cameron and the Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Osborne, subsequently enshrined in law the fiscal recommendations of the report, centred on high tax relief for research and development spending, up to 220 per cent of the money spent. This was designed to avoid the government having to pick winners, at which they are notoriously bad, but instead to help those who had already invested in themselves. Technology entrepreneurs who had spent their own money on research would be able, at the end of the tax year, to recover 100 per cent of the money they had spent on research even though they might not yet be paying tax. Tax relief was also given to people investing in technology start-ups. Start-ups are inevitably risky, and these measures were developed to encourage investors to support them as well as match-funding the entrepreneurs themselves. I am happy to report that between 2010, when the tax incentives were introduced, and 2018, British companies had doubled their expenditure on research and development.”

Dyson notes that government incentives were awarded to those who had already taken the risk. This is true in principle and in policy. People are more likely to back someone who is backing themselves. This is also a very important signal when looking for collaborators or partners. Have they invested in themselves?

Creative risk taking and imagination are as valid as market research and strategy:

“disruptive ideas can revolutionise a company and its finances through intuition, imagination and risk-taking as opposed to market research, business plans and strategic investment.”

Making and risk-taking are every bit as important as ‘traditional’ business activities. I would argue that the business activities are only valid if the making and risk taking are done first. The creator is why the business exists in the first place.

“One of these, the Mini, is a good example of why you should not listen to market research. BMC (British Motor Corporation) cancelled one of the two proposed Mini production lines as a result of the feedback from market research. The corporation was told that people would refuse to buy a car with such small wheels. In the event, BMC was never able to catch up with the demand that followed the launch of the trend-setting Mini. There are many more examples I won’t name here, yet each such artefact has its own story of against-the-odds progress and lessons on why having faith in your ideas and believing in progress is so very important.”

When you are introducing a truly new idea, market research is not a reliable predictor of success. People do not intuitively understand new ideas. Where there is no data, imagination and instinct must lead. Is your idea truly something new or is it something that already exists dressed in new clothes?

Forge your own path or others will try to do it for you:

“While my decision to work for Rotork Marine with the title ‘General Manager’ might have appeared at the time to be a waste of my degree and a way of jettisoning a possibly golden future in the world of design, I had observed that designers work on what manufacturers and clients ask them to design and this held no appeal. Rather grandly, I had decided I wanted to be the one developing the technology, engineering and design of a product and making and marketing it, too.”

There is a distinction in this passage about designing for others or originating your own ideas. Both are valid paths. What’s important is that Dyson knew which path he wanted. Which one do you want to take?

How much control do you need?

“In this sense, the Ballbarrow − my first consumer product, my first solo effort − was a failure but one from which I learned valuable lessons. There was a lesson about assigning patents, another about not having shareholders. I learned the importance of having absolute control of my company and of not undervaluing it. I knew how to make and sell, but not how to look after myself. We had charged too little for the product while competing with traditional tin barrows knocked up in sheds with no design input or new expense and low manufacturing overheads. In retrospect, the very idea of selling against a utility product was a mistake. Distribution was inefficient − all that selling to individual retail outlets − while the cost of exporting the Ballbarrow was prohibitive. The product was good, but the commercial proposition was a bad idea. From now on, though, I was determined not to let go of my own inventions, patents and companies. Today, Dyson is a global company. I own it, and this really matters to me. It remains a private company. Without shareholders to hold the company back, we are free to take long-term and radical decisions. I have no interest in going public with Dyson because I know that this would spell the end of the company’s freedom to innovate in the way it does.”

Retaining full ownership was especially important for someone as inventive and creative as Dyson. This gave him total freedom to innovate, however, not every creator thrives in isolation. There are thriving open-source communities and cooperatives that prove shared models of invention and innovation do work. The key is to know which model suits you.